In May of this year, a notice in the online edition of a local newspaper [1] caught my eye. It announced a cultural event featuring a puppet theater (German: Figurentheater, more on that later) and a lecture, both centered around the Wiener Neustadt Canal (German: Wiener Neustädter Kanal). The event was scheduled for 6:30 PM on May 26 in the ballroom (German: Festsaal des Amtshauses) located within the municipal building of Vienna’s Simmering district. “Admission free!” it added.

Puppet Theater

The Figurentheater turned out to be a form of theatrical art I hadn’t encountered before. The main character was both the puppeteer —who played multiple roles connected to the canal’s history – and his glove puppet: a large pig-like figure. I admit that the abstract nature of this element escaped me somewhat. In any case, I soon learned that the canal was a 19th-century waterway linking Wiener Neustadt (literally “Vienna’s New Town”) with Vienna, and that its construction and use involved various local dignitaries, especially Emperor Francis II of Austria.

I couldn’t focus on the historical details at first, because the puppeteer’s expressive storytelling and the whimsical props and set design kept triggering bursts of hearty laughter throughout the room – myself included. One memorable moment was when the audience was handed rolls of toilet paper to gently wave up and down, simulating the rippling water of the canal.

The Lecture

After the puppet show came a well-prepared lecture by an expert on the topic. Using a large screen presentation, he explained that Wiener Neustadt (about 40 km south of Vienna) was connected to the capital by a canal over 60 km long – longer than the straight-line distance due to its winding path. This waterway, completed in 1803, ended where today stands the Wien Mitte shopping and transport hub.

My notes from the lecture included the following key points:

- The canal was built to supply Vienna with bricks, lignite, and timber to meet growing demand.

- The nearby Vienna Woods (German: Wienerwald),were protected, so timber had to be sourced from the Rax region.

- The canal was only slightly wider than the barges it carried – about 2 by 23 meters, with a capacity of 23 to 30 tons.

- Each barge was pulled by a single horse, guided by a person, moving at 4 km/h.

- The barge crew consisted of two people: one at the bow pushing off the banks with a long pole, and one at the stern steering.

- The canal inspired a humorous nickname for the Austro-Hungarian monarchy: Kohle & Kanal-Monarchie (“Coal & Canal Monarchy”).

A highlight of the lecture was a live commentary on aerial photos showing the canal’s route from Wien Mitte to Simmering, and where traces of its topography are still visible today.

Asymmetry in Decision-Making

After the event, I felt that pleasant mental buzz that comes from discovering a fascinating local topic – one that lets you travel imaginatively through time and place. Oh, if only I had bought the speaker’s book [2], displayed on a table for €21.90! Regrettably, I acted like Harpagon from Molière’s The Miser. However, I plan to make up for it by visiting the Simmering District Museum [3].

As I reflected on why I hadn’t bought the book – despite being genuinely interested and finding the price reasonable – I realized I’d fallen into what I’d describe as a kind of psychological asymmetry in decision-making. Had the offer been framed differently – say, €10 for the puppet show and another €10 for the lecture, with the €20 book thrown in as a bonus – I would have happily paid. So why didn’t I part with those two tens?

Possibly due to a mix of:

- Mental accounting [4]: In one case, the book is a cost; in the other, a reward.

- Loss aversion [5]: I preferred avoiding a loss over gaining something.

This reflection led me to explore, albeit briefly, aspects of behavioral economics. I concluded that free admission was a smart way to attract attendees, and buying the book would have been a fitting gesture of appreciation—not to mention a personal gain. Perhaps I was also momentarily overwhelmed by the idea of acquiring yet another book, given how many are readily available, often without needing to buy them.

Along the Canal

Six days later, I visited Wiener Neustadt and was delighted to find that parts of the canal still exist – though no longer navigable.

- View from the Richard-Wagner-Gasse car bridge onto the Wiener Neustadt Canal towards the south.

On one stretch, I spotted an aqueduct over the Warme Fischa river, showing that the canal also crossed other waterways.

- View of one of the aqueducts of the Wiener Neustadt Canal, here crossing over the Warme Fischa.

The atmosphere was serene and gently alive – locals wandered leisurely along the riverbanks, dogs explored with curious noses, and ducks drifted gracefully across the water, leaving soft ripples in their wake.

Online Sources

Back home, I compiled a short list of German-language sources to learn more about the canal:

The topic isn’t widely known – even among Viennese, as I discovered in conversations with friends. Through these readings, I found several public artworks in Vienna that reference the canal’s history.

Public Artworks

About five weeks later, I took advantage of a beautiful Sunday afternoon to visit two sites where mosaics on building facades commemorate the Wiener Neustadt Canal.

Aspangstraße 15, 1030 Vienna – Mosaic by Hans Fischer (1892–1973), an Austrian artist associated with Vienna.

- Part of the mosaic (barge on the Wiener Neustadt Canal) on the building at Aspangstraße 15, 1030 Vienna. Hans Fischer, 1969.

The mosaic shows the distinctive outfits of the three-person barge crew: wide-brimmed hats for sun and rain, tall boots for working near water, and white trousers with colorful vests. These seemed more than just workwear – perhaps they marked a professional group or ethnic minority linked to this labor. I also noticed similarities to traditional raftsmen’s attire.

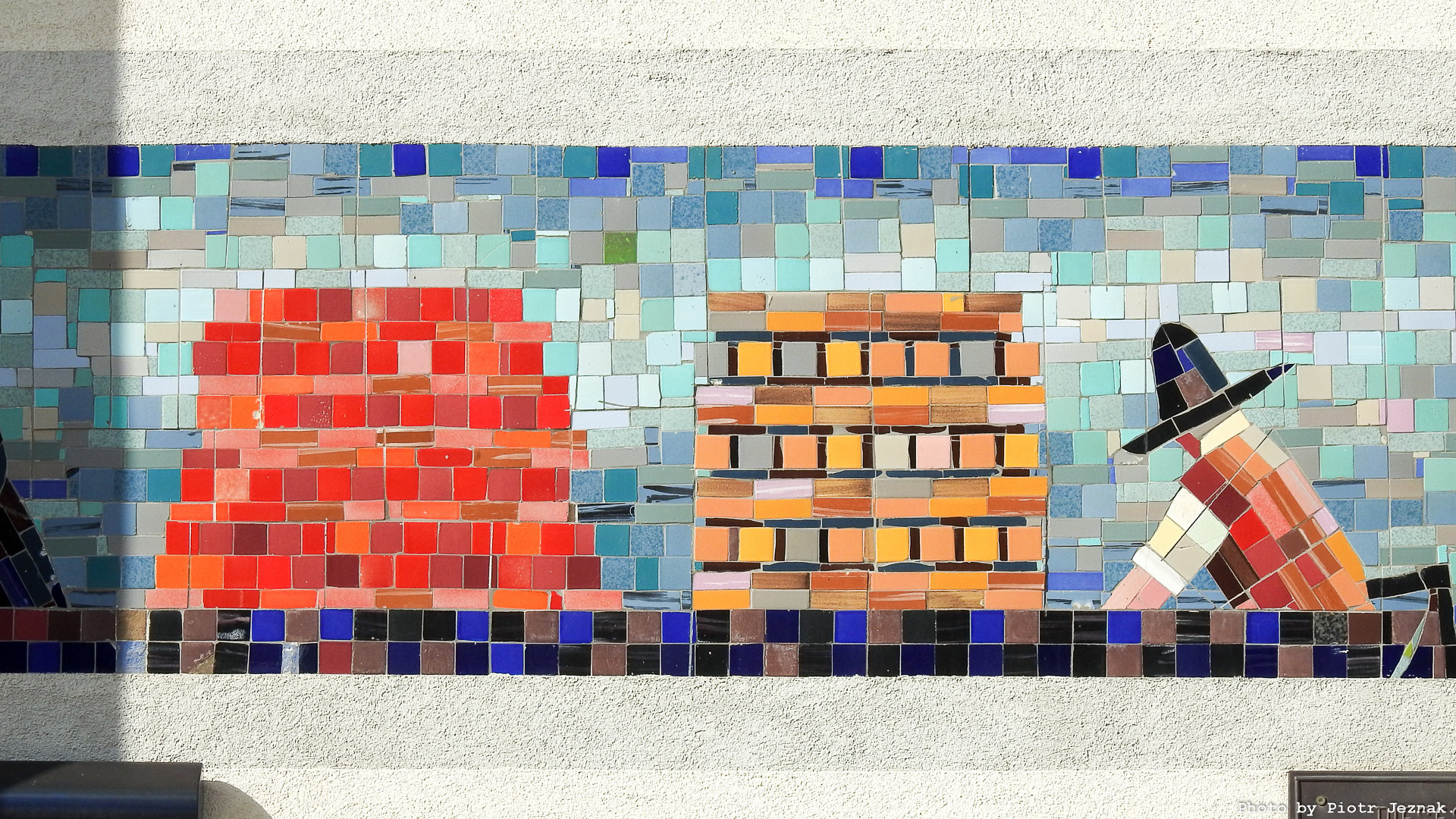

- Part of the mosaic (construction materials on the barge) on the building at Aspangstraße 15, 1030 Vienna. Hans Fischer, 1969.

The left stack on the barge clearly depicts bricks – red and rectangular. Could the right stack be timber?

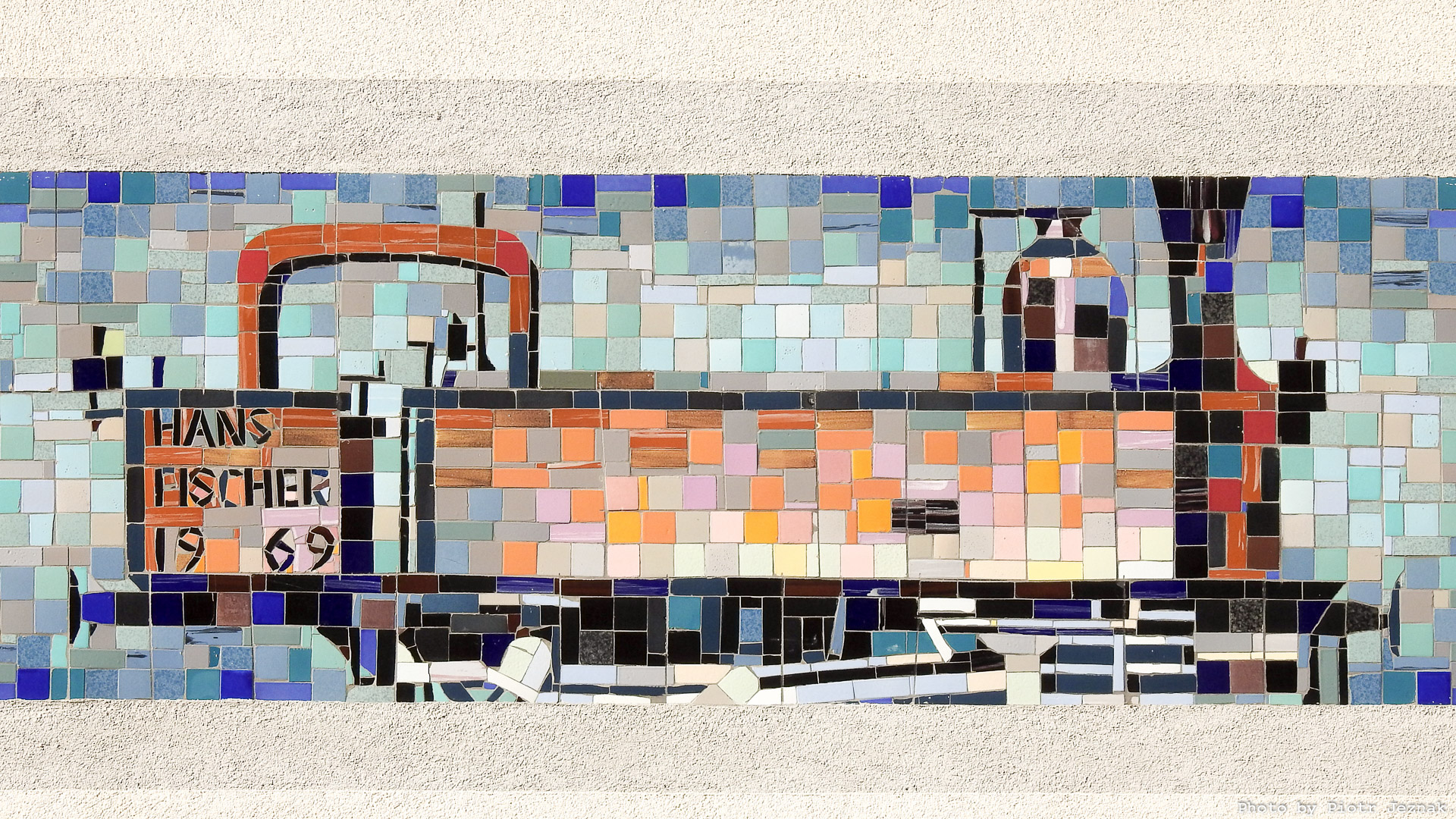

- Part of the mosaic (locomotive) on the building at Aspangstraße 15, 1030 Vienna. Hans Fischer, 1969.

The artist also included the steam locomotive EWA IIa of the private Vienna–Aspang Railway (German: Eisenbahn Wien–Aspang), founded in 1880. As railways expanded, horse-drawn barge transport became inefficient and unprofitable. The canal’s former port in Vienna was converted into an ice rink in 1867.

Hafengasse 3 / Klimschgasse 27, 1030 Vienna – Mosaic with the inscription 1803 Hafen des Wiener Neustädter Kanals 1867.

- Mosaic “1803–1867 Hafen des Wiener Neustädter Kanals” on the building at Klimschgasse 27, 1030 Vienna.

This relief shows riders and barges on the canal between panoramic views of Wiener Neustadt and Vienna, with the inscription below: 1803 Port of the Wiener Neustädter Kanal 1867. I was surprised that the two-person barge crew wasn’t depicted, and that the horses appeared to be ridden rather than led. Or perhaps all three crew members are shown on the return journey – without cargo? But where would they have gotten two extra horses?

District Museums

That short newspaper notice led me to the puppet show and lecture, helping me better understand my neighborhood – for example, the origin of the street name Am Kanal [6]. Online, I found detailed descriptions of the canal’s construction and function, and my photo excursions to Wiener Neustadt and Vienna’s Landstraße district yielded images that bring this 19th-century story back to life.

I also think it’s a great idea to gradually visit Vienna’s district museums (Wiener Bezirksmuseen [7]), where passionate locals share the history of their areas. At one museum per quarter, I could see them all in six years.

Cover photo: View from the Pottendorfer Straße bridge looking south along the Wiener Neustadt Canal.

- [↑] meinbezirk.at/simmering

- [↑] Hradecky, Johannes; Chmelar, Werner. Wiener Neustädter Kanal. Vom Transportweg zum Industriedenkmal. Wien Archäologisch 11. Wien: Phoibos Verlag , 2014

- [↑] External link: bezirksmuseum.at

- [↑] Originator: Richard H. Thaler. Reference: Mental Accounting Matters – Thaler, 1999.

- [↑] Originators: Daniel Kahneman i Amos Tversky. Reference: Prospect Theory – Kahneman & Tversky, 1979.

- [↑] External link: geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at

- [↑] External link: bezirksmuseum.at/de